Forestry is in the news this week; a rare-enough event in the British media. An apparent Government leak suggests that the Forestry Commission will be forced to sell off much of the private estate in England (probably not Wales and definately not Scotland). There could be benefits and of course disadvantages from such a change if it comes, and it reminded me of the influence of Government on British forestry. Afterall during the single life of one forest tree, anywhere from 45 to 120 years, Government policy may swing significantly three, four or even five times. Very rarely does the original intended purpose for a tree being planted get fulfilled.

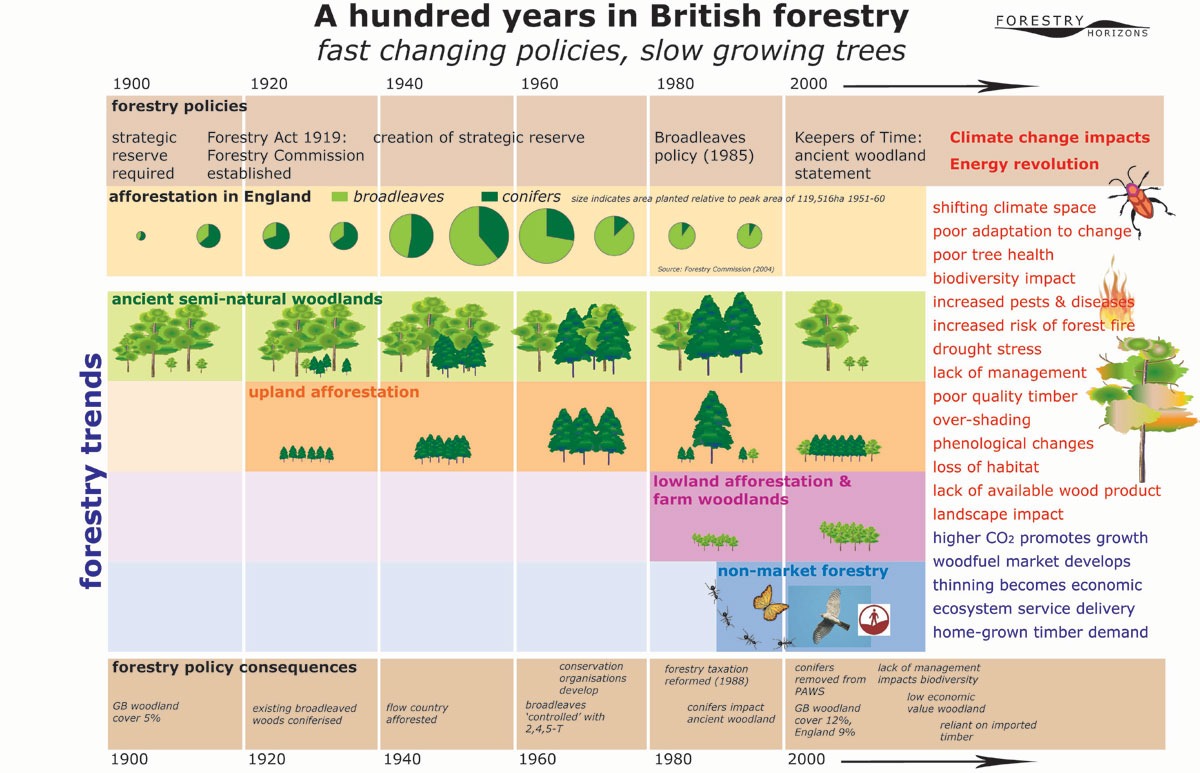

Slow-growing trees, fast-changing policies are evident when looking at the last 100 years of British forestry, as shown in the figure above (click to enlarge). The Forestry Commission (FC) was established in 1919 to create a strategic reserve after it was realised during the First World War that timber was a valuable commodity. It set about with great success to double Britain’s forest cover. This was mostly achieved using fast-growing conifer species such as Sitka spruce and lodgepole pine in our uplands. Less success was the lack of understanding that led to some of this planting being seen as “dark satanic rows” of conifers that blotted our upland landscapes, acidified our streams, ruined peat habitat and wrecked precious archaeology.

In some places during the 1950-70s, semi-natural woodland was being cleared to make way for commercial conifer plantations. The picture on the left shows the section of an oak tree that had been killed by the lethal injection of 2,4,5-T so that conifers could take its place!

Less than two decades later, growing understanding of these impacts coupled with greater environmental consciousness resulted in a shift towards broadleaves. The same conifers that were planted to replace oak, ash and beech were then removed as they were deemed inappropriate: – before they had been allowed to grow to maturity and able to produce a useful crop of softwood timber.

We entered a period of forestry policies led by environmental and social agendas in the 1990s and 2000s. The policy maker’s eye was off the importance of economics, the third leg of sustainability alongside environmental and social aspects. Government was slow to realise the opportunities that the emerging renewable energy industry could bring to forestry. Climate change was just emerging as an important driver for change and began to challenge major policies such those prescribing ‘native-only’ planting.

As for the British forestry sector itself, its main fault is that it has often meekly followed Government direction, lacking the co-ordination and vision to decide for itself what is best for sustainable forestry.

What I will say about the recent news of the possible sale of the public estate is that most of the forest land in England and Wales is in private hands. The vast majority (82%) of broadleaved woodlands, containing our oak, ash and beech etc., are in private ownership. Most of any sale if it happens will be of conifer plantations (think of Kielder Forest). Talk of ‘logging’ and ‘loggers’ cutting down Britain’s woodlands is typical media hype. All tree felling Britain is controlled by law (felling licence) and replanting is almost always required.

Gabriel Hemery

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.

Very interesting, and well presented, but would an alternative title also fit the facts?

“Fast growing trees, slow changing policies.”

The planting of fast growing (bog and habitat damaging) spruce on the uplands and fast growing (native woodland destroying) hemlock on the ancient woodland sites made policy sense as a reserve of timber in time of submarine blockade, between about 1919 and the development of nuclear weapons in 1945.

But the painfully slow policy change only happened in the mid 1980s?