There are about 60 species of tree that are native to Britain but many more have been introduced over centuries. Even those that we consider quintessentially British, such as Sweet Chestnut or ‘English’ walnut are actually non-native; both having been introduced by the Romans. It is important that we protect and enhance forests that contains native tree species. At the same time, many scientists now agree that it would be foolhardy to be focus exclusively on planting native species and using locally-native-only material.

Locally-native

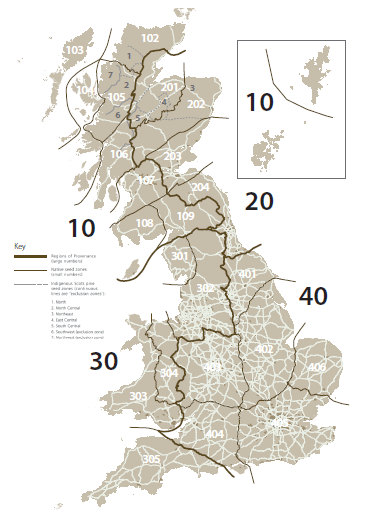

Technically Great Britain is divided into four regions of provenance (origin): defined areas within which similar ecological and climatic characteristics are found (see map). The areas provide a framework for specifying sources of Forest Reproductive Material (FRM) but must not be treated too literally. Many of these boundaries are actually national borders or even motorways. In reality of course, a tree on the west side of a motorway is not likely to be genetically distinct from one on the east side, just because the motorway is the defining line between two regions or areas. Many people don’t realise that plenty of oak pollen is blown over the English Channel from France, and birch pollen across the North Sea from Scandinavia. So, the notion of locally-native genetic material is not as simple as some conservationists suppose.

Technically Great Britain is divided into four regions of provenance (origin): defined areas within which similar ecological and climatic characteristics are found (see map). The areas provide a framework for specifying sources of Forest Reproductive Material (FRM) but must not be treated too literally. Many of these boundaries are actually national borders or even motorways. In reality of course, a tree on the west side of a motorway is not likely to be genetically distinct from one on the east side, just because the motorway is the defining line between two regions or areas. Many people don’t realise that plenty of oak pollen is blown over the English Channel from France, and birch pollen across the North Sea from Scandinavia. So, the notion of locally-native genetic material is not as simple as some conservationists suppose.

Future-proof trees and forests

More importantly, looking forward, we must ensure that our treescapes (trees in cities, scattered trees in the landscape, and woodlands and forests) are resilient and future-proof. With increasing threats from pests and diseases, combined with a changing climate, it is more important than ever that our trees are able to cope with these threats, and that they can continue to provide for our needs. Our choice of tree species is a critical factor and using some ‘exotic’ genetic material in our native tree species may be very important to ensure genetic diversity (e.g. trees native to Britain sourced from northern continental Europe). Equally important, planting non-native trees in certain forests will help ensure genetic diversity at the landscape scale, and thereby ensure that our forests are resilient. I wrote about this in a practical guide.

Online toolkit

Two leading scientists from Forest Research, Bill Mason and Richard Jinks, have created a fantastic online resource: providing information on over 60 tree species that are either widely grown in British forests at the present time or which could play an increasing role in the future, focusing on those species which could be expected to produce usable timber in British conditions.

Visit Forest Research’s Tree Species and Provenance toolkit

Gabriel Hemery

Bibliography

I’ve published quite a few papers on this subject, both in scientific journals and as practical articles for foresters. Here are a few that can be downloaded or viewed on the climate change section of the Forestry Horizons online library:

- G E Hemery et al., “Growing scattered broadleaved tree species in Europe in a changing climate: a review of risks and opportunities,” Forestry 83, no. 1 (2010): 65-81.

- G E Hemery, “Forest management and silvicultural responses to projected climate change impacts on European broadleaved trees and forests,” International Forestry Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 591-607.

- G E Hemery, “Climate change – what should I do? A practical guide for woodland owners and managers.” Nicholson Nurseries (2007).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.

Those borders seem to be based more on the forestry commission’s operating areas rather than trees. The borders should at least reflect the geography a bit better. The Pennines especially have been thrown in with any old regions (although I wouldn’t have a single Pennine region though). The range of climates and geography alone in places such as that suggests that the trees in those areas may be slightly different.

Look at the North Pennines – do they really expect us to believe that the trees at the Alston passes have arrived there via Lancashire and not Cumbria and Northumbria?

I suppose the provenances shouldn’t be too strict though because we need the genetic diversity. There’s probably not that much difference between a tree from Gwynedd and one from Lancashire for instance.