The Inclosure Acts of England (referred to above), introduced mostly between 1750 and 1860, fundamentally changed our relationship with the countryside, affecting some 2.8 million hectares. With the proposed sale of the public forest estate on the horizon, are we entering a new era of sweeping and far-reaching changes to England’s rural landscape and fundamentally changing the relationship with our forests?

The Inclosure Acts of England (referred to above), introduced mostly between 1750 and 1860, fundamentally changed our relationship with the countryside, affecting some 2.8 million hectares. With the proposed sale of the public forest estate on the horizon, are we entering a new era of sweeping and far-reaching changes to England’s rural landscape and fundamentally changing the relationship with our forests?

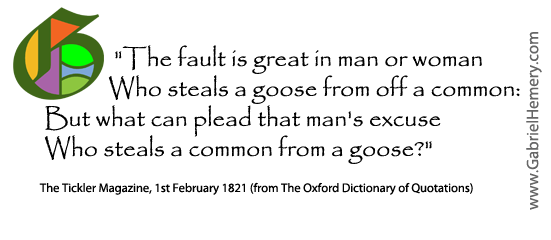

Many people apparently believe that the proposed public forest sale is indeed “stealing the common from the goose“, although I admit it isn’t normally said in this way! According to my poll, which is still open, there appears to be very strong support (standing at 89% today) for the State to continue its ownership of forest land in Britain.

Writing in The Observer last Sunday, Andy Wightman argued that we should look overseas to successful community ownership models and that the proposed sale of the public forest estate provides an opportunity to revolutionise ownership. Can we really encourage communities to take up the challenge of creating a new relationship with their local forests? Communities and individuals will need to develop and cultivate a relationship that to date has been one-way (i.e. appreciating and utilising a woodland’s assets) or at best third-party (e.g. donating money to a woodland-owning charity). Instead they will need to give something back directly and develop a two-way relationship by investing resources, long after current passions concerning the sale of forests have died away.

What resources will communities be needing to mobilise?

- money for investing in the purchase of a woodland;

- money to pay for woodland management (e.g. for tree management, health and safety checks, tree inspections, habitat regulations, biodiversity management, recreation provision, access structures, car parking, emptying dog waste and litter bins etc.);

- time to apply for grant funding;

- time to volunteer for practical tasks;

- time and money to gain practical skills and knowledge.

All of these resources are attainable by enthusiastic and dedicated communities, and there are likely to be exciting opportunities for some communities to invest in their local woodland, which certainly fits well with the current Government’s vision for a Big Society. These aren’t new ideas of course, as illustrated in the section below if you care to read more. Can we adopt these ideas across England – crowded with people and relatively devoid of woodlands? Time will tell.

Gabriel Hemery

If you are interested in community forest ownership models there are many reports from around the world. The case study from Germany by Hartebrodt et al. (2005) suggests that contrary to the view of some, productivity increased in woodlands transferred to the local community, with increases in wood use in construction and wood heat schemes. In terms of the methods and impacts of introducing community forestry, Baker and Kusel (2003), provide some compelling insights of attempts to stimulate and encourage community forestry in the USA.

In relation to the UK, the Mersey Forest, which is a community forest in a different sense as it concerns a region, has recently published a report summarising their views on the public forest estate sale. Community forestry is quite advanced in Scotland, with a number of successful examples (e.g. the Dunbar Community Woodland). A helpful review is provided by a Forest Research report (Calvert 2009).

References

Baker, M. and Kusel, J. (2003). Community Forestry in the United States: Learning from the Past, Crafting the Future. Island Press. 264pp.

Calvert, A. (2009). Community Forestry Scotland: A Report for Forest Research. 53pp.

Hartebrodt, C., Fillbrandt, T. and Brandl, H. (2005). Community forests in Baden-Württemberg (Germany): A case study for successful Public-Public-Partnership. Small Scale Forestry, 4, 3, pp.229-50. DOI: 10.1007/s11842-005-0015-8.

Do tell me if you know of other useful sources of relevant information on community forestry in the developed world, or share them with everyone via a comment.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.